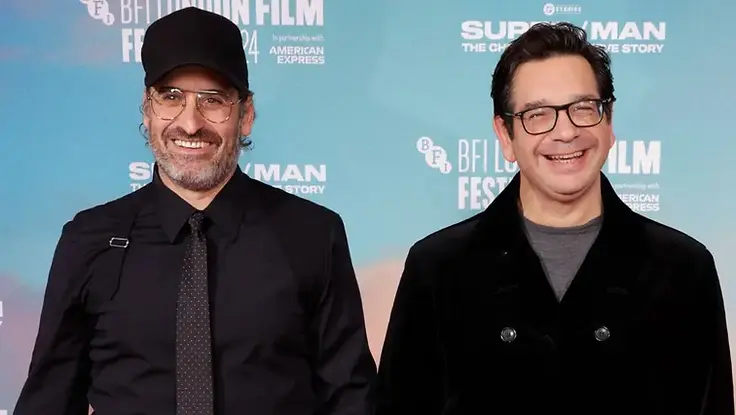

Whilst in attendance at the BFI London Film Festival, the directors of Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story, Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, were kind enough to speak with me along with some fellow writers and critics at a roundtable interview. Below are the contents of that insightful and wide-ranging discussion.

The following answers have been edited for brevity. Questions from the assembled critics are in bold italics,

I want to say thanks so much for the wonderful film – I really enjoyed it. My question was whether there were any surprises you encountered during the development of the film in terms of how you originally envisaged it and in the edit.

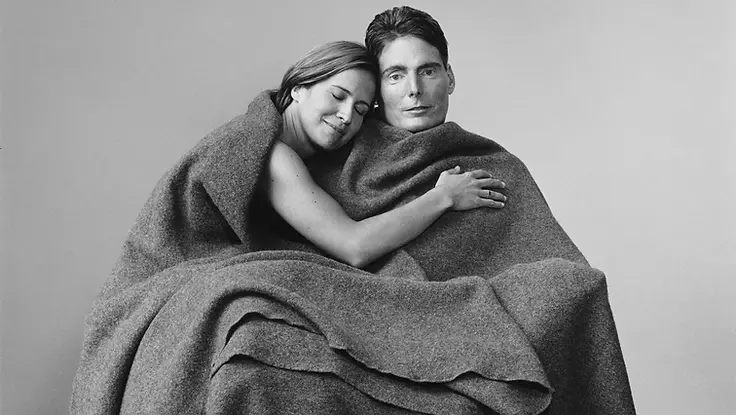

Ian Bonhôte, co-director: I think the fact that we ended up making the film more almost about the family and actually that the fact that they took such a massive role into the film is something I wasn’t expecting at the start. Because we got approached to make a film about Christopher Reeve and then you start digging into his life story and then you start meeting the three children [William Reeve, Matthew Reeve and Alexandra Reeve Givens] – and then you just realise, “Oh my God, they’re amazing.”

Oh my God, the impact of the accident and then the death was so massive on the family, on them personally. So basically, that is something definitely the film shape change quite drastically. But again, we are not dogmatic: When we start a film we have a vision of what we want to do, but we are always ready to adapt to [use archive footage] or something that one of our contributors say, but we always try to make the film about the really important people and very quickly we realised [William, Matthew and Alexandra] were the three most important people.

I really loved the narrative structure and how you had Christopher Reeve at the height of his career and also after the accident and I would just like to know how you created that emotional through-line – because I thought it was very intentional how you paralleled his career with maybe what he was doing with the charity or how his life was going or his relationship with his family parallel to in his famous Hollywood life where he was just doing Hollywood stuff. So how did you just create that emotional line between both?

Peter Ettedgui, co-director: Well, the most important thing is when you set up to make any film, whether it’s fictional or nonfictional, is to think about the shape, the structure of the story you’re going to tell and how that is going to release the emotional content. It’s not just form for form’s sake – you’ve got to think about what is the content. What are you trying to express through the story? I think that from the very beginning what we actually wanted to avoid was a typical biopic ‘cradle to grave’ episodic structure because we felt that that wouldn’t do any favours, that wouldn’t let the story breathe in any way that an audience would really be able to experience the emotions that we wanted them to experience. So pretty soon we kind of realised that the most dramatic point of the film, alas – but amazingly for filmmaking – was the accident because that is the lowest ebb that you can possibly imagine in anyone’s life really.

So if you start at that point and then you carry that through and you start seeing that there’s this sort of extraordinary shape to it, discovering going from almost suicidal despair to realising there’s still a reason to live even if it’s just for his family and for his friends, and whether it’s Dana saying “You’re still you and I love you”, or whether it’s Robin Williams making him laugh. You have those moments and then that’s one sort of very positive thing that happens after this extraordinarily negative thing. And then you have this sort of discovery of a new sense of purpose for your life and the realisation that actually in some profound aspect what this tragic thing that’s happened to you is actually something that you can use for good both in your own life in terms of your own relationships, but also in terms of the broader world.

That’s just the most wonderful gift of a story those nine years. So we knew that although this was a story ostensibly about the guy who played the OG superhero, we knew that the story that wasn’t going to be the story, how he got cast and how he got it was important that we told that story, but the really important emotional story was going to be those nine years and then it was a question of how we used breaks in that story to bring in the past and also to bring in the past in a way that as you rightly said, it counterpoints or mirrors things that were happening to him on how his fall and new rise after the accident parallels his very sharp rise and then decline in his career in the past. And so we knew we would have those things that would counterpoint each other.

We get a clip from Christopher’s audiobook where he mentioned that while in hospital his life kind of played out before him but not in order. So I was wondering in the documentary that specific portion, did you edit that in a nonlinear way or was that unintentional? Could you elaborate on that?

Ian: Actually, some of the structure that Peter alluded to was inspired as well from the audiobook itself – but that sequence you alluded to was actually almost a gift because you could use that to justify the structure we gave afterwards. So it was 100% intentional and there’s not a single frame or a single sound or a single music note that is not intentional in our films. I don’t want to sound bigheaded, but you have to direct every single aspect of the film – just you don’t have the makeup, you don’t have the costume like in fiction, but as Peter said, you’ve got the archive, you’ve got how the archive comes in, comes out. How do you mix intimate personal archive with interviews from outlets when they were at the height of the fame, the interviews of the people you’ve used? We always try to think about it as a fiction film, where there’s different dialogues – but that moment in particular you mentioned is extremely visual. At the same time we could do something a bit more like a music video or something a bit crazy because you are almost hallucinating with [Christopher Reeve]. But then afterwards he justified the fact that we have different moments of his life that clashes.

Peter: I would just say by the way, well spotted because that line that you just quoted, it was in our first pitch, the very first thing we wrote that was we wanted to quote that as Ian says, to justify our approach because sometimes I think, and it’s true with us that with this film that some of the executives that we were working with, it was very, very collaborative and happy collaboration, but some of them were sceptical about the structure.

Ian: “How’s it going to work?” And you show them a first [cut] which is two and a half hours – I’d be sceptical. The thing is that it’s longer when you make more and more film, more and more you in the industry you realise there’s a lot of people with opinions but really few opinions you should listen to. Not to become too egoistical, but there’s only, I mean with two directors and a very strong editor, Otto Bonome is a great editor – but that’s already three voices. If we agree the three of us that probably covers a lot of other human beings. In fiction, you have a script that everybody judge and then people judge the execution of that script, the performance, the lighting, the use of the choreography, the use of the shot… In nonfiction, the script is kind of written as we have a sort of draft – but it’s kind of written on the way and it’s basically showing four or five drafts before the final drafts. And you always have to say when people watch the film, you’ve already have comments yourself. When you show two and a half hours you’re not going to have a two and a half hours film but you had to show them something and they give you 80% of the notes. They’re like, “Yeah, we fucking know it’s two and a half hours long, we’re going to remove 45 minutes.” Do you see what I mean? Sorry, pardon my French, but I think that’s the thing.

So I guess the thing that when you talked about Christopher Reeve, it’s all the birth of the superhero film, which is now so prevalent and the genre is so saturated now. I was just wondering – you have so many clips from his other roles as well – was it important for you to really showcase his other roles and the other sides to his dramatic persona and did you have any favourites of his other works that you liked?

Peter: Yeah, I mean the truth is obviously that when we were researching the film, we were watching a lot of Christopher in different films. From great films like Death Trap to the TV movies of the week, which are… not so great – but he had to pay the bills. So you got a sense of a real working actor’s career in that and that was very important for us.

I think some people may very well, and kind of justifiably, think “Actually you guys, you didn’t do proper justice to some of his other performances”, but you have to make choices and then you have to stick to your lane. So we absolutely wanted to show some of his other work in the context of the fact that that work was never, once he’d made Superman, that was it. That was the top of his career and he constantly fought against that. He felt trapped by Superman and he pushed himself to do whether it was working in the theatre, whether it was taking smaller parts in films – he wanted to kind of somehow break free of Superman and I don’t think he ever really did. And that was the context in which we wanted to depict his other work and we had to have that context. It is really important for the themes of the film in a way.

Ian: And the OG thing – I mean the other thing which is really interesting is none of you are above 30.

[Some attendees point out that they are above 30. Laughs.]

You only, you guys look very young – but the point is a lot of you have grown up through the era of massive amount of Marvel and all rest of it, especially since 2005 to today it’s been very successful, but at the time [Christopher Reeve] was the first one – but he’s probably responsible for that as well because suddenly the studio saw huge amount of money, $400-$500 million for the first film in the Seventies. That’s probably the equivalent of $1.5-$2 billion now. So it’s probably an equivalence, not money equivalence, but how much it was at the time to get to that number so quickly. I mean I think that’s what I try to do is just like wow, how first as documentary make, you don’t get to talk about Superman much – because we’re not going to make the next Superman–

Peter: Well, we might. [Laughs]

Ian: I think James Gunn is better than us – but the thing is looking about how [the superhero genre] evolves and made change into the way we perceive movies and stuff.

Peter: And I would just add that we found this bit of footage that I was determined to get in the film but actually it just had nothing to do with the film that we were making: Kevin Feige talking about how before they make any [MCU] film, they sit down and they watch Christopher Reeve’s performance in the first Superman film because that’s the superhero and I think it’s also very true for James Gunn who’s moved over from Marvel to DC and it’s kind of like–

Ian: “Why did he move?” It must be because of the excitement of restarting Superman. There’s something magical about Superman, I think, still absolutely from a lot of the other superheroes. They mix them up with other superheroes. Superman is Superman – on his own kind of thing. Then they’ve tried to make Superman and Batman to make more money and all the rest of it. But I think the way James [Gunn] is going back to the original Superman, I think it’s the right [decision]. We don’t know much about it, but I think he’s made the right choice.

Peter: We were told after [Super/Man finished production, about James Gunn’s Superman film], because the film was made in completely independently. Warner’s only came in after our premier at Sundance and boy did they come in. They kind of love-bombed us really at that point it was very flattering – and I did think we were in with the chance of making a Superman film at that point. [Laughs]

But, joking apart. I think they told us a couple of weeks later after they’d acquired the film that they’d shown the film to the cast of [James Gunn’s] Superman on location in Atlanta where they were filming and how much it had inspired everybody. It’s nice to know that on one hand that Chris has sort of inspired both the MCU and the new DC Studios Universe. It’s great to know that, but obviously we can all make our personal decisions as to whether this whole superhero domination of cinema is a good or a bad thing.

Ian: It’s dying out. There’s less of them now. Actually, it’s moved to TV now.

I think it’s different now. I think it’s different the way a young actor – because he’d probably be someone within 20 and 30 – it’s almost a step to success. You need to be one of them for the paycheque and for the exposure. So many people are making their careers because they do this one. Do you see what I mean? So it’s a very different thing.

It was a risk at the time [of the original Superman] because there was nothing done before. Right now if you look [there are] a huge amount of very, very good actors that might go on to make a really sort of small independent film.

Now potentially, the crazy thing for actors is to be in a play. All the theatre plays in London make such a big deal when there’s a Hollywood person coming in.

Peter: By the way, great questions, everyone. No pressure.

I just wanted to say congratulations on the film. As a comic book fan – lover of both MCU and DC – this film really struck a chord. I do remember as a kid watching Superman and I remember the day when the news was announced about Christopher Reeve being paralysed and then obviously his untimely death as well.

To focus on the aftermath of the accident and the disability – there’s a part of the film where [Christopher Reeve] talks about the industry not being disability-friendly and you see that really come together where he’s trying to get ready for the Oscars and the transportation, the mobilisation, the lack of insurance and so forth – to just get to the Oscar stage and making it public and so forth. And I just wanted to know, through making this documentary, has your world shifted? Have you seen your perspective change on disabilities?

Ian: I think it started with a previous film already. We made a film called Rising Phoenix about the Paralympic movement and the perspective started to change now. I mean we moved offices and we wanted to stay in Soho. There are hardly any offices which are disability-friendly for anyone who would need a lift to go somewhere, let alone if you’ve got visual impairment or hearing impairment, etc. So it is very tricky to have a disability in this industry as well. I think if you do fiction, as you remember on Rising Phoenix, we had one of our researchers, Ella Beaumont, who is a wheelchair user.

Peter: Who also worked with us on Super/Man.

Ian: She – and we – wanted her to be on set, so we had to be triply careful. It made our choices for location a lot tighter to be able to accommodate everyone – which potentially, some creative people might not want to embrace that because they need the film to represent what they have in their mind.

So, I think, what the film does for me personally is the shift in how we need to keep our society accountable for many reasons about inclusion in general – for many reasons we don’t even need to mention on this table. I have been in this industry in the UK for a long time. The industry does not have one person at the top saying “You can’t get in”, “You’re not the right person” or “You’re a woman” or “You’re disabled” or whatever. I don’t think it’s that – I think it’s laziness, a lack of understanding of different stories. Inclusion means you get a bigger perspective in a sense – you broaden your horizons as an individual. Let’s say someone in a wheelchair is 60% less efficient. The presence of the person will increase 140% the knowledge and the understanding of the rest of the team. So maybe if the person can do 60%, then the rest of the team will understand way more.

Peter: This kind of goes back to what you were saying about Christopher’s problems getting to the Oscars. I mean talking about Ella and the reason that you’re saying 60% is because the daily routine is so much tougher. I mean Ella lives near Aylesbury, so she had to get to our office in Tottenham Court Road. She’s paraplegic and sometimes there wasn’t somebody to help her get on the train, sometimes the train was cancelled, sometimes some of the stations did not have lifts – so we had to find an office near Tottenham Court Road. It is more challenging both for the person and also the employer.

So you know, we already knew that from Rising Phoenix – we’d heard a lot of extraordinary stories and we had also made a kind of commitment in that film to have people with disabilities working with us on the team and we took that onto Super/Man.

One of the shifts that happened during the making of Super/Man was that we thought that Christopher was heroic because of his advocacy and his activism, but we really discovered the controversy that some of that work inspired – Ella was saying to us “This whole thing about trying to ‘fix disability’ – that’s really quite offensive to people with disabilities.” Ella was born with a disability, so it is very different – but again, that opened our eyes to another way of looking at Christopher’s story. Those elements of controversy were very important. It took a long time for Christopher to see his life post-accident as valid as his life pre-accident. As he actually says, “It took breaking my neck for me to learn some of this stuff” – which is such a key line in the film.

Ian: We needed as well, just to be truthful – we needed to find a way to call it Super/Man without being sued by [Warner Bros]. [Laughs]

Peter: All our conversations: “Are we going to get away with using this Superman material? Are [Warner Bros] going to let us licence it? Are we going to be able to use this music? Are we going to be able to use the title?” Then [Warner Bros] came on board and they turned out to be the heroes.

At this point (purely by coincidence, I assure you), the Warner Bros PR in attendance informed us that our time was up and that the roundtable was over.

Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story is in UK cinemas from November 1.

Thank you to Warner Bros UK for our invitation to a private Super/Man screening and organising the roundtable.